How many “facts” do we accept at face value?

For example, do we really remember 10% of what we hear, 20% of what we see, 50% of what we do…?

It’s human nature to accept knowledge that’s universally propagated. If enough people say it enough times, it assumes the aura of conventional wisdom.

Our peers wouldn’t be wrong, right?

Hold your horses

This is where Critical Theory steps in.

A critical theorist examines accepted truths in light of their socio-historical contexts. In his thought-provoking paper Critical Theory: Ideology Critique and the Myths of E-Learning, Dr Norm Friesen maintains:

“The central argument of critical theory is that all knowledge, even the most scientific or ‘commonsensical,’ is historical and broadly political in nature. Critical theorists argue that knowledge is shaped by human interests of different kinds, rather than standing ‘objectively’ independent from these interests.”

As you can tell by that quote, Critical Theory is steeped in political science and social justice. However it all boils down to challenging any knowledge that presents itself as “certain, final, and beyond human interests or motivations” and is “considered so obviously commonsensical or natural that it is placed beyond criticism”.

In other words, Critical Theory is about myth busting.

Myths in e-learning

As the Canada Research Chair in E-Learning Practices at Thompson Rivers University, Dr Friesen applies the principles of Critical Theory to three e-learning myths:

-

We live in a knowledge economy.

-

E-Learning enables “anyone, anywhere, anytime” access to education.

-

Technology drives educational change.

I’m going to provide a brief overview of Friesen’s arguments, but then I’m going to do something either incredibly brave or incredibly stupid: point out where I don’t agree with the author – an academic heavyweight about a thousand times more credible than I.

But hey, Critical Theory is all about challenging what we’ve been told. Besides, by the end of this piece you’ll realise that I essentially agree with Dr Friesen. So please bear with me!

The knowledge economy

Friesen argues that the concept of a “knowledge economy” defines knowledge as a commodity. Rather than something that should be shared openly, it has market value and thus can be bought and sold.

Friesen recognises the social implications of such a philosophy: the emergence of a classist society in which knowledge workers (ie those who have the knowledge) succeed and prosper, while service workers (ie those who don’t have the knowledge and are relegated to manual labour) struggle and subsist.

My problem with Friesen’s argument is that it doesn’t appear to bust the myth of the knowledge economy. If anything, it reinforces its truth.

He describes the current state of affairs – the encroachment of technology on traditional educational artifacts; criticisms of the schooling system in its current form; the postindustrial shift from manufacturing to services; the widening gulf between rich and poor.

Then he advocates means by which we might overcome it – recognise the value of other forms of work that complement knowledge work; cultivate a range of skill sets that relate to those other forms of work; view knowledge as an instrument of democratisation rather than as a saleable commodity.

In other words, the knowledge economy is not a myth, and there is a danger that a large proportion of the population will become disaffected by it if we don’t do anything about it.

Anyone, anywhere, anytime

Friesen argues that the catchphrase “anyone, anywhere, anytime” promotes a privileged group of people (ie white males) as the universal representation of all e-learners. However, the digital divide dictates that “anyone” does not include people in disadvantaged communities; “anywhere” does not include nations outside the OECD; and “anytime”, I suppose, is redundant in light of the first two.

My problem with Friesen’s argument in this instance is that it takes the catchphrase out of context. In the corporate sector, for example, “anyone, anywhere, anytime” is certainly not a myth. It’s entirely plausible that all the employees of a particular company can access their e-learning resources from anywhere at anytime – and if they can’t, it’s an anomaly that the IT department needs to fix quick smart.

In this scenario, the experience of the population (ie the staff) is indeed universalised. Race, gender and income have absolutely nothing to do with it.

Besides, I’d imagine there are plenty of blokes in Lithuania (not to mention in trailer parks across the US) who would take umbrage to the assumption that all white males are rich and hyperconnected. Is that, ironically, a myth that critical theorists are guilty of perpetuating?

Technology drives educational change

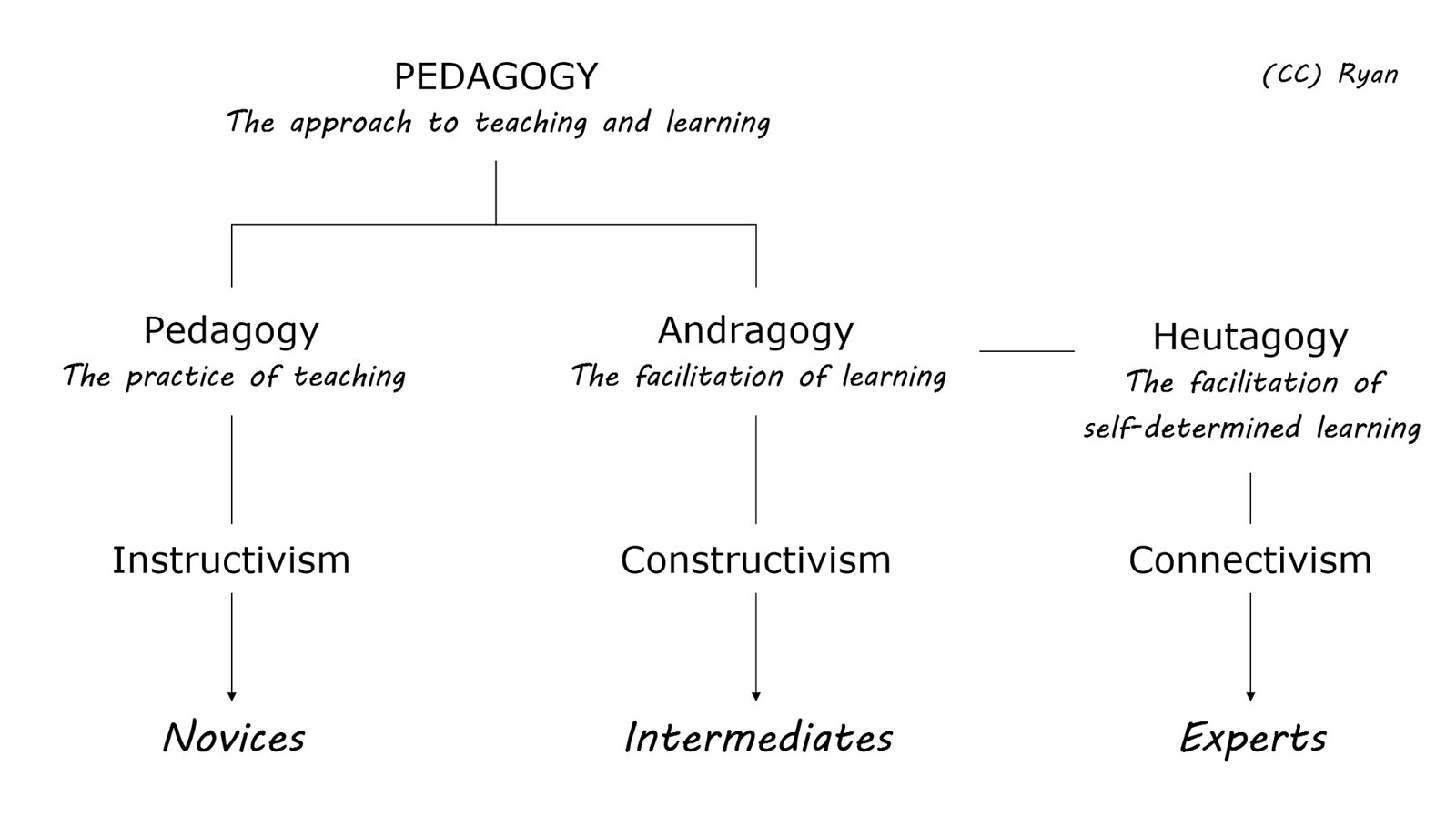

Finally, Friesen argues that the myth “technology drives educational change” disempowers educators. It dictates that it is not they who drive the future of their own profession, but rather technological progress. Those who adopt new technologies will go forth and conquer, while those who resist will lag behind.

In contrast, Friesen maintains that technology is only one component of a complex system. As such, it is incapable of acting alone to initiate change, but rather must interact with people in their environment who will appropriate it accordingly.

My problem with Friesen’s argument this time around is that since the dawn of time, technologies from paper to blackboards, from computers to smartphones, have changed education. The way we teach and learn today is vastly different from how we did even a mere 20 years ago.

I agree that technology hasn’t driven those changes single handedly – after all, humans must be around to use it – but the flip side is that the changes would not have occurred if the technology was not introduced.

Regardless of how teachers and students respond to new technologies – whether they adopt or adapt them, hack them or mash them – their world will be different. Maybe we can’t predict how it will change, but we know that it will.

Shoot the messenger

When I finished reading Friesen’s paper, I couldn’t shake the nagging feeling that I really didn’t disagree with him. I know that sounds preposterous given my observations above, but it was so.

I couldn’t put my finger on it until I realised that Critical Theory isn’t really about busting myths after all; it’s about critiquing messages.

If I do a global find for “myth” in Friesen’s paper and replace it with “message”, suddenly our views align:

-

Knowledge is increasingly seen as a commodity in today’s workplace, and it’s leading us headlong into a social crisis.

-

Anyone, anywhere, anytime access to e-learning is feasible for a privileged few.

-

Technology drives educational change via its interactions with teachers and students.

The questions I feel the critical theorist must ask are: Who propagates particular messages, and why do they do it? Under what circumstances are they true or false? What are the consequences of that truth or falsehood? What can or should we do about it?

You can bet your bottom dollar that those who pontificate about the knowledge economy are those who stand to profit from it handsomely.

Just like you may appreciate the CLO of a corporation using e-learning to facilitate anywhere, anytime access to knowledge for staff, but perhaps remain rather skeptical of some official from the UN grandstanding about it on behalf of the world’s poor.

Just like you may see through a salesman’s rhetoric about the next big thing, but rest assured if that doesn’t change your world, something else will.