The term “Agile” means different things to different people.

To some it’s the powerhouse of efficiency and productivity; whereas to others it’s a vague label at best, or an empty buzzword at worst.

And I can see why the conflict arises: because two forms of agile exist – one with a small “a”, the other with a big “A”.

Small “a” agile

Small “a” agile is a 400-year old word in the English language that means to move quickly and easily. In the corporate context, it lends itself to being open to change and adapting to it, while maintaining a healthy sense of urgency and prioritising delivery over analysis paralysis.

It’s a mindset that underscores the concept of the MVP – Eric Ries’s construct of good enough – to get the product or service that your customers need into their hands as soon as possible, so they can start extracting value from it now.

Then you continuously improve your offering over time. Retain what works, and modify or cancel what doesn’t. That way you fail fast and small, while iterating your way towards perfection.

Big “A” Agile

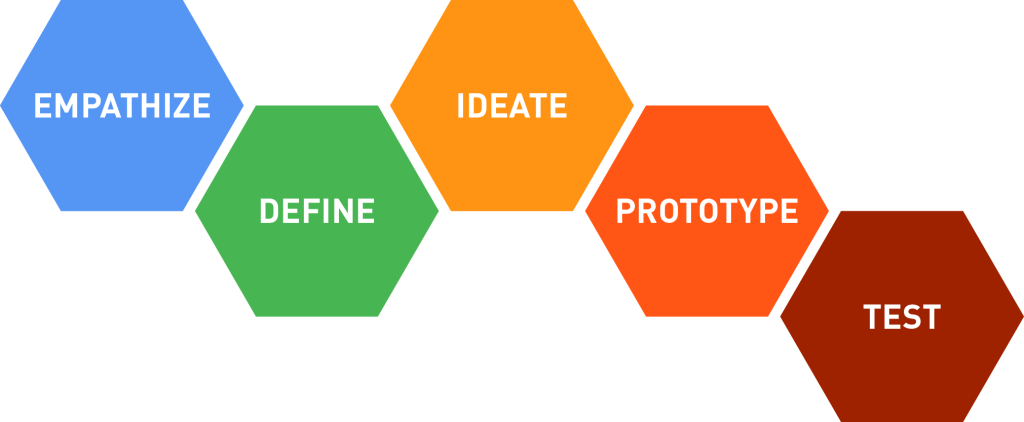

In comparison, big “A” Agile is a methodology to manage that way of working.

It provides tools, structures and processes – think sprints, kanbans and retrospectives – to pin down the volatility, uncertainty, complexity and ambiguity of our work, thereby maintaining clarity over what needs to be done, and baking in accountability to ensure it gets done.

Hence it may be helpful to think of small “a” agile as an adjective and big “A” Agile as a noun; bearing in mind that big “A” Agile might also be used as an adjective to describe a person, place or thing that adopts the methodology.

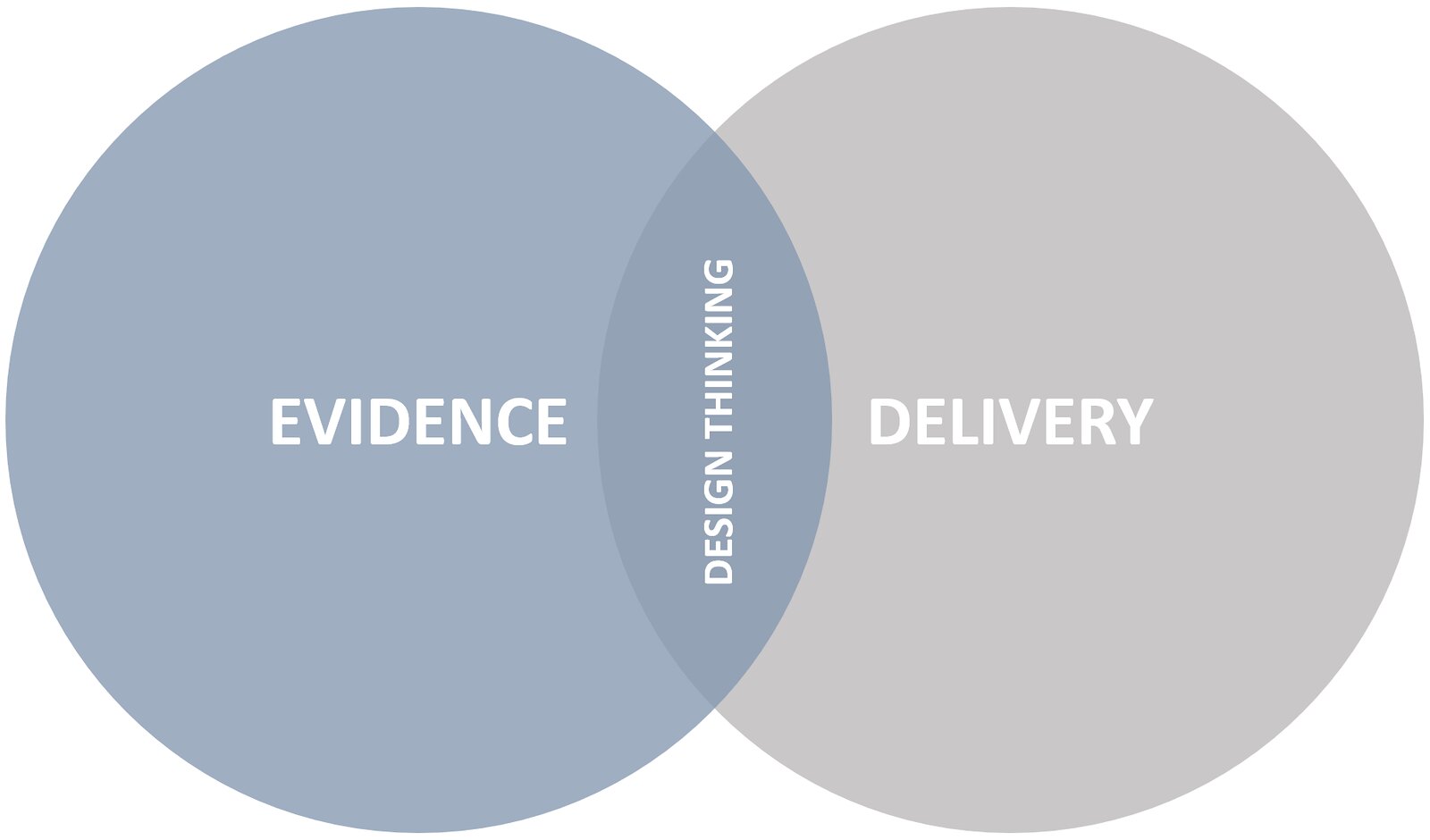

Regardless, some of our peers rail against Agile as a redundant neologism. As with other trends such as Design Thinking, they argue it’s merely old world practices repackaged in a new box. It’s what we’ve always done and continue to do as consummate professionals.

But I politely challenge those folks as to whether it’s something they really do, or rather it’s something they know they should do.

If a new box helps us convert best practice into action, I’m a fan.