You can narrow down someone’s age by whether they include spaces in their file names. If they do, they’re under 40.

That is a sweeping declaration, and quite possibly true.

Here’s another one… Gamers are a sub-culture dominated by young men.

This declaration, however, is stone-cold wrong. In fact, 63% of American households are home to someone who plays video games regularly (hardly a sub-culture). Gamers are split 59% male / 41% female (approaching half / half) while 44% of them are over the age of 35 (not the pimply teenagers one might expect).

In other words, the playing of video games has normalised. As time marches on, not gaming is becoming abnormal.

So what does this trend mean for e-learning professionals? I don’t quite suggest that we start going to bed at 3 a.m.

What I do suggest is that we open our eyes to the immense power of games. As a profession, we need to investigate what is attracting and engaging so many of our colleagues, and consider how we can harness these forces for learning and development purposes.

And the best way to begin this journey of discovery is by playing games. Here are 5 that I contend have something worthwhile to teach us…

1. Lifesaver

Lifesaver immediately impressed me when I first played it.

The interactive film depicts real people in the real world, which maximises the authenticity of the learning environment, while the decision points at each stage gate prompt metacognition – which is geek speak for realising that you’re not quite as clever as you thought you were.

The branched scenario format empowers you to choose your own adventure. You experience the warm glow of wise decisions and the consequences of poor ones, and – importantly – you are prompted to revise your poor decisions so that the learning journey continues.

Some of the multiple-choice questions are unavoidably obvious; for example, do you “Check for danger and then help” or do you “Run to them now!”… Duh. However, the countdown timer at each decision point ramps up the urgency of your response, simulating the pressure cooker situation in which most people I suspect would not check for danger before rushing over to help.

Supplemented by extra content and links to further information, Lifesaver is my go-to example when recommending a game-based learning approach to instructional design.

2. PeaceMaker

Despite this game winning several prestigious awards, I hadn’t heard of PeaceMaker until Stacey Edmonds sang its praises.

This game simulates the Israeli-Palestinian conflict in which you choose to be the Israeli Prime Minister or the Palestinian President, charged with making peace in the troubled region.

While similar to Lifesaver with its branched scenario format, its non-linear pathway reflects the complexity of the situation. Surprisingly quickly, your hipsteresque smugness evaporates as you realise that whatever you decide to do, your decisions will enrage someone.

I found this game impossible to “win”. Insert aha moment here.

3. Diner Dash

This little gem is a sentimental favourite of mine.

The premise of Diner Dash is beguilingly simple. You play the role of a waitress in a busy restaurant, and your job is to serve the customers as they arrive. Of course, simplicity devolves into chaos as the customers pile in and you find yourself desperately trying to serve them all.

Like the two games already mentioned, this one is meant to be a single player experience. However, as I explain in Game-based learning on a shoestring, I recommend it be deployed as a team-building activity.

4. Keep Talking and Nobody Explodes

As its name suggests, Keep Talking and Nobody Explodes is a multi-player hoot. I thank Helen Blunden and David Kelly for drawing it to my attention.

In the virtual reality version of the game, the player wearing the headset is immersed in a room with a bomb. The other player(s) must relay the instructions in their bomb defusal manual to their friend so that he/she can defuse said bomb. The trouble is, the manual appears to have been written by a Bond villain.

It’s the type of thing at which engineers would annoyingly excel, while the rest of us infuriatingly fail. And yet it’s both fun and addictive.

As a corporate e-learning geek, I’m also impressed by the game’s rendition of the room. It underscores for me the potential of using virtual reality to simulate the office environment – which is typically dismissed as an unsuitable subject for this medium.

5. Battlefield 1

I could have listed any of the latest games released for Xbox or PlayStation, but as a history buff I’m drawn to Battlefield 1.

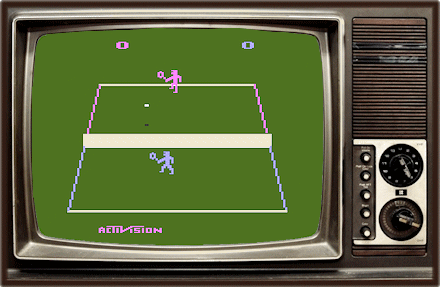

It’s brilliant. The graphics, the sounds, the historical context, the immersive realism, are nothing short of astonishing. We’ve come a long way since Activision’s Tennis.

My point here is that the advancement of gaming technology is relentless. While we’ll never have the budget of Microsoft or Sony to build anything as sophisticated as Battlefield 1, it’s important we keep in touch with what’s going on in this space.

Not only can we be inspired by the big end of town and even pick up a few design tips, we need to familiarise ourselves with the world in which our target audience is living.

What other games do you recommend we play… and why?