English is a funny language.

Coloured by countless other languages over centuries of war, politics, colonialism, migration and globalisation, many words have been lost, appropriated or invented, while others have changed their meaning.

In Australian English for example, fair dinkum means “true” or “genuine”. Linguaphiles speculate the phrase originated in 19th Century Lincolnshire, where “dinkum” referred to a fair amount of work, probably in relation to a stint down the mines. Add a tautology and 10,000 miles, and you have yourself a new lingo.

Thousands of other English words have their origins in ancient Greek. One pertinent example for L&D practitioners is pedagogy (formerly paedagogie) which derives from the Hellenic words paidos for “child” and agogos for “leader”. This etymology underscores our use of the word when we mean the teaching of children.

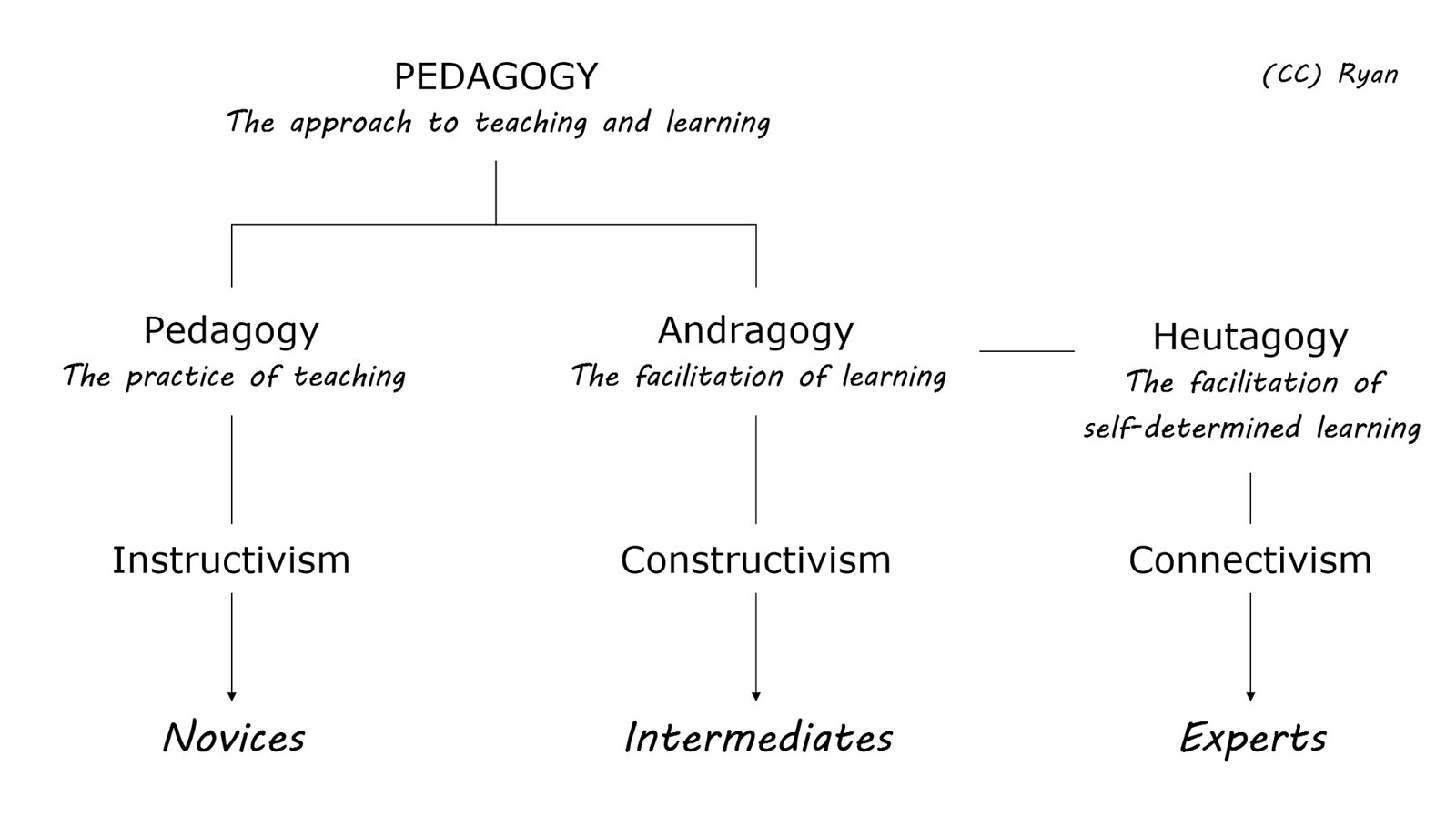

And yet our language is nuanced. We may alternately use pedagogy to mean the general approach to teaching and learning. Not necessarily teaching, not necessarily children. In this broader sense it’s an umbrella term that may also cover andragogy – the teaching of adults – and heutagogy – self-determined learning.

For example, when Tim Fawns, the Deputy Programme Director of the MSc in Clinical Education at the University of Edinburgh, blogged his thoughts about pedagogy and technology from a postdigital perspective, he defined pedagogy in the university setting as “the thoughtful combination of methods, technologies, social and physical designs and on-the-fly interactions to produce learning environments, student experiences, activities, outcomes or whatever your preferred way is of thinking about what we do in education”.

When Trevor Norris and Tara Silver examined positive aging as consumer pedagogy, they were interested in how informal learning in a commercial space influences the mindset of its adult patrons.

And when I use the word pedagogy in my capacity as an L&D professional in the corporate sector, I’m referring to the full gamut of training, coaching, peer-to-peer knowledge sharing, on-the-job experiences and performance support for my colleagues across 70:20:10.

So while I assume (rightly or wrongly) that the broader form of the term “pedagogy” is implicitly understood by my peers when it’s used in that context, I spot an opportunity for the narrower form to be clarified.

Evidently, modern usage of the word refers not only to the teaching of children but also to the teaching of adults. Whether they’re students, customers or colleagues, the attribute they have in common with kids is that they’re new to the subject matter. Hence I support the Oxford English Dictionary’s definition of pedagogy as the practice of teaching, regardless of the age of the target audience.

If pedagogy includes adults, then logic dictates we also review the exclusivity of the term andragogy. Sometimes children are experienced with the subject matter; in such cases, an andragogical approach that draws upon their existing knowledge, ideas and motivations would be applicable. Hence I dare to depart from the OED’s definition of andragogy as the practice of teaching adults, in favour of the facilitation of learning. Again, regardless of the age of the target audience.

With regard to heutagogy, I accept Hase & Kenyon’s coinage of the term as the study of self-determined learning; however in the context of our roles as practitioners, I suggest we think of it as the facilitation of self-determined learning. That makes heutagogy a subset of andragogy, but whereas the latter will have us lead the learners by pitching problems to them, hosting Socratic discussions with them and perhaps curating content for them, the former is more about providing them with the tools and capabilities that enable them to lead their own learning journeys.

This reshaping of our pedagogical terminology complements another tri-categorisation of teaching and learning: instructivism, constructivism and connectivism.

As the most direct of the three, instructivism is arguably more appropriate for engaging novices. Thus it aligns to the teaching nature of pedagogy.

When the learner moves beyond noviceship, constructivism is arguably more appropriate for helping them “fill in the gaps” so to speak. Thus it aligns to the learning nature of andragogy.

And when the learner attains a certain level of expertise, a connectivist approach is arguably more appropriate for empowering them to source new knowledge for themselves. Thus it aligns to the self-determined nature of heutagogy.

Hence the principle remains the same: the approach to teaching and learning reflects prior knowledge. Just like instructivism, constructivism and connectivism – depending on the circumstances – pedagogy, andragogy and heutagogy apply to all learners, great and small.