It seems like everyone’s spruiking the “new normal” of work.

The COVID-19 pandemic is keeping millions of previously office-bound employees at home, forcing L&D professionals to turn on a dime.

Under pressure to maintain business continuity, our profession has been widely congratulated for its herculean effort in adapting to change.

I’m not so generous.

Our typical response to the changing circumstances appears to have been to lift and shift our classroom sessions over to webinars.

In The next normal, which I published relatively early during lockdown, several of my peers and I recognised the knee-jerk nature of this response.

And that’s not really something that ought to be congratulated.

For starters, the virus exposed a shocking lack of risk management on our part. Digital technology is hardly novel, and our neglect in embracing it left us unprepared for when we suddenly needed it.

Look no further than the Higher Education sector for a prime example. They’re suffering a free-fall in income from international students, despite the consensus that people can access the Internet from other countries.

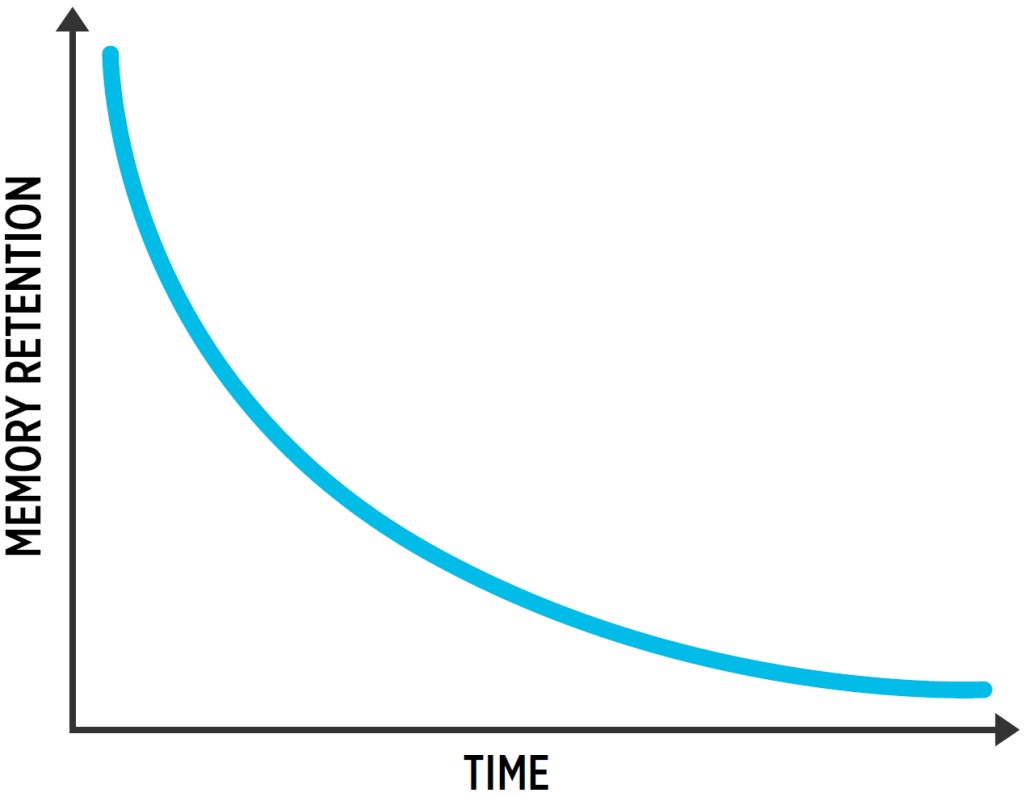

Beyond our misgivings with technology, moreover, the virus has also shone a light on our pedagogy. The broadcast approach that we deliver virtually today is largely a continuation of our practice pre-pandemic. It wasn’t quite right then, and it isn’t quite right now. In fact, isolation, digital distractions and Zoom fatigue probably make it worse.

I feel this is important to point out because the genie is out of the bottle. Employee surveys reveal that the majority of us either don’t want to return to the office, or we’ll want to split our working week at home. That means while in-person classes can resume, remote learning will remain the staple.

So now is our moment of opportunity. In the midst of the crisis, we have the moral authority to mature our service offering. To innovate our way out of the underwhelming “new normal” and usher in the modern “next normal”.

In some cases that will mean pivoting away from training in favour of more progressive methodologies. While I advocate these, I also maintain that direct instruction is warranted under some circumstances. So instead of joining the rallying cry against training per se, I propose transforming it so that it becomes more efficient, engaging and effective in our brave new world.

Good things come in small packages

To begin, I suggest we go micro.

So-called “bite sized” pieces of content have the dual benefit of not only being easier to process from a cognitive load perspective, but also more responsive to the busy working week.

For example, if we were charged with upskilling our colleagues across the business in Design Thinking, we might kick off by sharing Chris Nodder’s 1.5-minute video clip in which he breaks the news that “you are not your users”.

This short but sweet piece of content piques the curiosity of the learner, while introducing the concept of Empathize in the d.school’s 5-stage model.

We’re all in this together

Next, I suggest we go social.

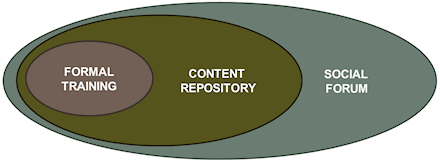

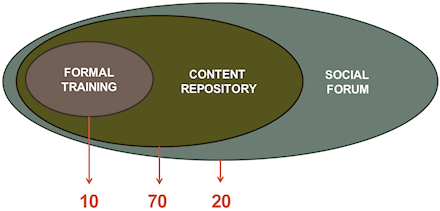

Posting the video clip to the enterprise social network seeds a discussion, by which anyone and everyone can share their experiences and insights, and thus learn from one another.

It’s important to note that facilitating the discussion demands a new skillset from the trainer, as they shift their role from “sage on the stage” to “guide on the side”.

It’s also important to note that the learning process shifts from synchronous to asynchronous – or perhaps more accurately, semi-synchronous – empowering the learner to consume the content at a time that is most convenient for them (rather than for the L&D department).

There is no try

Next, I suggest we go practical.

If the raison d’être of learning & development is to improve performance, then our newly acquired knowledge needs to be converted into action.

Follow-up posts on the social network shift from the “what” to the “how”, while a synchronous session in the virtual classroom enables the learner to practise the latter in a safe environment.

Returning to our Design Thinking example, we might post content such as sample questions to ask prospective users, active listening techniques, or an observation checklist. The point of the synchronous session then is to use these resources – to stumble and bumble, receive feedback, tweak and repeat; to push through the uncomfortable process we call “learning” towards mastery.

It’s important to recognise the class has been flipped. While time off the floor will indeed be required to attend it, it has become a shorter yet value-added activity focusing on the application of the knowledge rather than its transmission.

Again, it’s also important to note that facilitating the flipped class demands a new skillset from the trainer.

A journey of a thousand miles

Next, I suggest we go experiential.

Learning is redundant if it fails to transfer into the real world, so my suggestion is to set tasks or challenges for the learner to do back on the job.

Returning to our Design Thinking example, we might charge the learner with empathising with a certain number of end users in their current project, and report back their reflections via the social network.

In this way our return on investment begins immediately, prior to moving on to the next stage in the model.

Pics or it didn’t happen

Finally, I suggest we go evidential.

I have long argued in favour of informalising learning and formalising its assessment. Bums on seats misses the point of training which, let’s remind ourselves again, is to improve performance.

How you learned something is way less interesting to me than if you learned it – and the way to measure that is via assessment.

Returning to our Design Thinking example, we need a way to demonstrate the learner’s mastery of the methodology in a real-world context, and I maintain the past tense of open badges fits the bill.

In addition to the other benefits that badges offer corporates, the crux of the matter is that a badge must be earned.

I am cognisant of the fact that my proposal may be considered heretical in certain quarters.

The consumption of content on the social network, for example, may be difficult to track and report. But my reply is “so what” – we don’t really need to record activity so why hide it behind the walls of an LMS?

If the openness of the training means that our colleagues outside of the cohort learn something too, great! Besides, they’ll have their own stories to tell and insights to share, thereby enriching the learning experience for everyone.

Instead it is the outcome we need to focus on, and that’s formalised by the assessment. Measure what matters, and record that in the LMS.

In other words, the disruptive force of the COVID-19 pandemic is an impetus for us to reflect on our habits. The way it has always been done is no substitute for the way it can be done better.

Our moment has arrived to transform our way out of mode lock.