I’m sure you know the feeling. You’re sitting in a classroom watching a presentation – which started late to allow the “stragglers” to show up – when about 10 minutes in it dawns on you…

What am I doing here?

Either you’re already familiar with what’s being presented, or it’s so straight-forward it didn’t require 30 or 60 minutes of your time. But whether it be due to politeness, shyness, peer pressure, or a sense of obligation, you remained bolted to your seat until the bitter end.

It’s such a waste of time – both for you and for the presenter.

Traditional classroom

Despite my obvious predilection for e-learning, I am actually a fan of the traditional classroom.

I appreciate that sometimes it is more efficient for someone who knows more than you to teach you something. As a novice, you don’t know what you don’t know. But the expert does, and he or she can get you up to speed.

Also, away from your desk you’re free from those universal distractions such the phone, email and uninvited guests. Furthermore, you have the opportunity to ask questions and receive immediate feedback from the human standing right before you.

However the traditional classroom has plenty of downsides too. For example, you typically can’t influence the content that is being delivered, you’re beholden to the pace of the presenter, and there’s always that *@#! idiot who hasn’t bothered with the pre-work yet is happy to prolong the misery for everyone else by asking inane, redundant questions.

Virtual classroom

A modernised version of the traditional classroom is the virtual classroom.

Delivering the content over the internet allows people to attend wherever they are geographically located, without incurring travel costs and losing time in transit. A virtual class also allows people to attend to other tasks if need be, and to slip away on the sly if it becomes clear the session isn’t adding any value.

Of course, the virtual classroom also has its fair share of downsides too. From technical glitches to the challenges of e-moderation, it is common knowledge that virtual presenters fantasise about the good ol’ days when everyone was in the same room at the same time.

Flipped classroom

A postmodern twist on the classroom delivery model is the flipped classroom.

Taking root in the school and university environments where regular classroom sessions are mandated and homework is the norm, the “flipped” concept posits the content delivery as the homework (typically in the form of a video clip) which frees up the in-person session for value-added instruction such as discussion, Q&A, worked examples, role plays etc.

I truly believe the flipped classroom is on the cusp of revolutionising the education sector.

No classroom

Notwithstanding the advantages of the three aforementioned classroom options, there is yet another option that is often ignored by educators: no classroom.

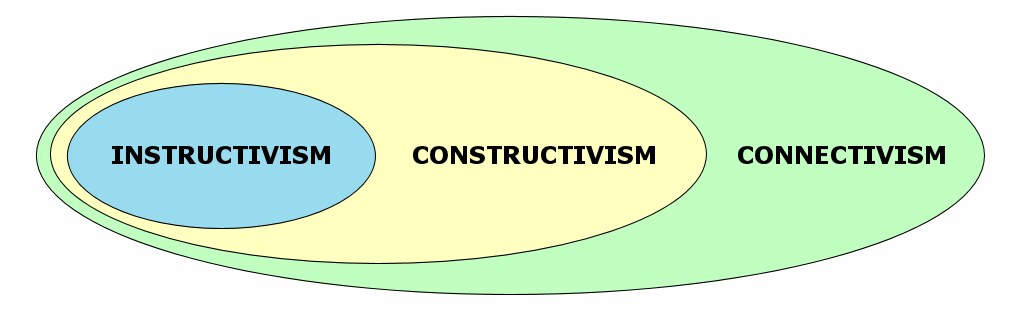

Readers of this blog will be familiar with my obsession passion for informal learning environments, but in this instance I’m not referring to the constructivist approach. Still true to the instructivist paradigm, I maintain the “no classroom” option can work.

It’s so simple: record your class on video. Then deploy it to your audience, so they are empowered to watch it when convenient, pause, fast-forward, rewind, and even play it again later.

The model is similar to a flipped classroom, but there is no in-person follow-up. And you know what? Frequently that’s all that’s needed. When the content is so straight-forward that it doesn’t require a classroom session, why on earth would you waste everyone’s time with one?

In cases where the content is more complex and follow-up is necessary, why not combine the video with formative exercises? An online discussion forum? A buddy program? Again, you probably don’t need to drag everyone into a classroom.

My point is, under the right circumstances, video can provide effective instruction.

But don’t just take my word for it. Why not get a second opinion from Ted, Lynda, Salman or David.