Academia is teeming with learning theories.

Some of them are old, some of them are new. Some are flash-in-the-pan, others stand the test of time and remain applicable to this very day. Some of them are controversial, while others have assumed the aura of conventional wisdom. Some of them are simple, while others are incomprehensible to mere mortals.

It can be quite a challenge for the modern learning professional to identify an appropriate learning theory, draw practical ideas from it, and apply it to their daily work.

Where do you start? Which theory do you choose? What is its central premise? How does it relate to other theories?

Taxonomy

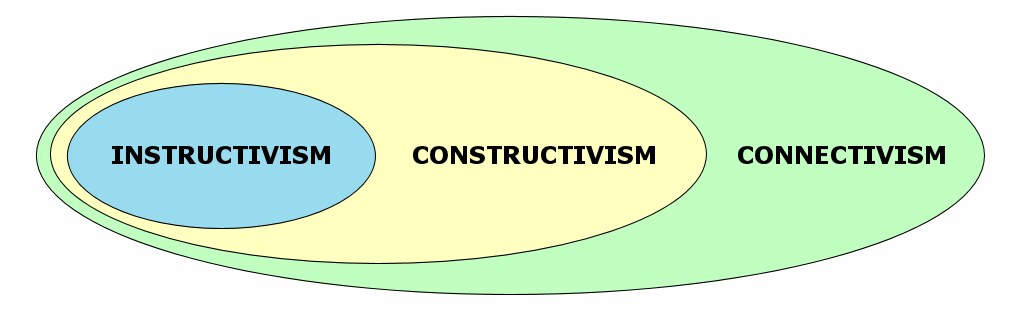

To clear some of the obfuscation that surrounds learning theory, I have developed the following Taxonomy of Learning Theories.

This taxonomy identifies key theories that apply to workplace learning, categorises them according to common properties, and illustrates the relationships among them.

I hope that this taxonomy, along with the corresponding notes below, will assist you in using learning theory to inform your instructional design decisions.

Overarching themes

Almost all learning theory is derived from one or more of the following psychological schools of thought:

- Behaviourism

- Cognitivism

- Constructivism

- Connectivism

These four psychologies form the overarching themes of my taxonomy.

Behaviourism

Classical conditioning maintains that a neutral stimulus can be associated with another stimulus that elicits a particular response. This concept was demonstrated in the early 1900s by Ivan Pavlov, who reported that after a period of conditioning, a dog will associate the sound of a beating metronome (neutral stimulus) with food, and respond to it in the same manner (salivate).

Operant conditioning maintains that behaviour is controlled by its consequences: behaviours that are rewarded are likely to be repeated, while behaviours that are punished are unlikely to be repeated. This concept was demonstrated by Edward Thorndike, who placed a cat in a “puzzle box”. The cat discovered that by pulling a ring, a side door fell open which allowed it to escape. So when Thorndike put the cat back in the box, it pulled the ring again.

Social Learning Theory is another theory that has its roots in behaviourism. I somewhat amateurishly consider it operant conditioning by proxy, whereby the learner (especially a child) observes the rewarded actions of someone else, and thus behaves similarly. It’s important to note that Social Learning Theory now extends beyond the behaviourist domain to encompass cognition, particularly through the work of Julian Rotter and Albert Bandura.

Cognitivism

Since behaviourism focuses on external behaviour, it considers the mind a black box. In contrast, cognitivism peers inside the box to explain the inner structures and processes of learning.

Models of memory

Numerous cognitivist learning theories derive from the Modal Model of Memory developed by Richard Atkinson and Richard Shiffrin since 1968. They proposed that human memory comprises three components: (1) Sensory memory, which perceives the information that is collected by our senses, such as visual information (eg a drawing) and auditory information (eg a bell toll); (2) Short-term memory, which processes the information that has been supplied by the sensory memory; and (3) Long-term memory, our more-or-less permanent knowledge storage area.

Atkinson & Shiffrin’s concept of short-term memory was superseded in 1974 by Alan Baddeley and Graham Hitch’s concept of working memory, which comprises the central executive and three slave systems: (1) The phonological loop, which processes verbal information; (2) The visuospatial sketchpad, which processes visual imagery and spatial information; and (3) an integrative component called the episodic buffer.

In 1956, George Miller reported that the “span of immediate memory” is limited to the magical number 7±2 items. From this, he deduced that the amount of information that could be processed at any one time could be increased by “chunking” it.

In the 1970s, John Anderson started to develop ACT-R, which maintains that long-term memory comprises declarative memory which is explicitly stored and retrieved (eg crashing your bike into a tree on your birthday when you were a child) and procedural memory which is unconsciously stored and retrieved (eg the motor skills required for riding a bike generally).

Schema theories

Models of memory provide the foundation for subsequent cognitivist theories that (arguably) have more direct implications for instructional design.

In 1977, Richard Anderson extended the work of earlier theorists such as Frederic Bartlett and Jean Piaget. His Schema Theory of Learning maintains that within long-term memory (or more specifically, declarative memory), knowledge is arranged in a hierarchical network of constructs called “schemas”.

Similarly, David Ausubel’s Subsumption Theory proposes that learning involves the linking of new information to relevant points in the learner’s existing cognitive structure. During the learning process, new information is subsumed under more general information in the hierarchical arrangement of the learner’s prior knowledge.

Charles Reigeluth’s Elaboration Theory complements Ausubel’s principle of ideational scaffolding. Reigeluth maintains that instruction should be organised in increasing order of complexity. In particular, the simplest (or epitomised) version of the domain should be provided initially, and elaborated upon subsequently. This approach develops a broad, meaningful context into which the learner can assimilate the narrow, detailed information.

Cognitive load

In 1988, John Sweller synthesised key principles of memory and schema under a new proposal called Cognitive Load Theory.

Cognitive Load Theory maintains that the mental effort required for learning imposes a cognitive load on working memory. The total cognitive load consists of three components: (1) Intrinsic cognitive load, which is imposed by the intrinsic characteristics of the content that is to be learned; (2) Germane cognitive load, which refers to the mental effort required to organise the elements of the content into a schema, integrate it into long-term memory, and automate its processing; and (3) Extraneous cognitive load, which does not contribute to the learning process (eg the mental effort required to block out loud music).

If the total cognitive load of the learning task exceeds the processing capacity of working memory, learning fails. This suggests that instruction should be designed with a view to reduce cognitive load and thereby avoid overload.

Constructivism

Constructivism has a rich history. Numerous theorists have contributed to its development over the last century (eg Jean Piaget, Lev Vygotsky, Jerome Bruner, Ernst von Glaserfeld), and several brands are recognised in the domain (eg cognitive constructivism, social constructivism, radical constructivism).

Regardless of the theorist or the brand, however, constructivism essentially maintains that people learn by constructing their own knowledge on the basis of their experiences. Constructivist learning theories recognise that everyone’s framework of prior knowledge is unique, thus they have their own needs, goals and contexts.

Adaptation

In his study of child development, Jean Piaget posited that every learner has a mental representation of the world which he or she constructs through their experiences.

When a person experiences cognitive conflict (a discrepancy between their mental representation and what they are currently experiencing), they undergo a process of adaptation. If the new experience aligns with their mental representation, the learner assimilates it in the form of new knowledge into their existing schema. If, however, the new experience does not align with their mental representation, the learner must rearrange their existing schema to accommodate the new knowledge.

Clearly, adaptation is complementary to Schema Theory; however, the constructivist perspective emphasises the learner centredness of the activity.

Situated Learning Theory

A valuable means by which a learner can close the gaps in their existing schema, and broaden and deepen their knowledge, is to engage with other people, ask questions, debate ideas, and share experiences.

Situated Learning Theory focuses on this social, practice-based approach to learning. The theory views learning in terms of participation in a community of practice, and considers knowledge to be highly dependent on its context.

Andragogy

Andragogy focuses on adult learning, and it adopts a strong constructivist perspective.

It boils down to 5 assumptions about adult learners as articulated by Malcolm Knowles: (1) Adult learners are self directed; (2) Adults bring experience with them to the learning environment; (3) Adults are ready to learn to perform their role in society; (4) Adults are problem oriented, and they seek immediate application of their new knowledge; and (5) Adults are motivated to learn by internal factors.

I have stated previously that I believe Knowles’ 5 assumptions generally hold true – but not for all adults, and certainly not all of the time. An andragogical approach is appropriate for adults who are intellectually mature, self directed and intrinsically motivated, with time to learn and their heads in the right space.

Connectivism

While cognitivism focuses on knowledge inside the mind, connectivism focuses on knowledge outside the mind.

George Siemens describes connectivism as “a learning theory for the digital age”. He maintains that in today’s world, there’s simply too much knowledge to take in – and it changes too quickly anyway.

So forget about trying to know everything; instead, exploit technology to extend your knowledge beyond your own brain. Build a network of knowledge sources which you can access as the need arises.

Recognising meaningful patterns among distributed sets of information, rather than storing it all in your head, re-defines what it means to “learn”.

Today I had the honour of collecting a Best Blended Learning Solution Award (Gold Level) at the 2010 LearnX Asia Pacific Conference.

Today I had the honour of collecting a Best Blended Learning Solution Award (Gold Level) at the 2010 LearnX Asia Pacific Conference.